Despite a slow start, the 2022 midterm primary season is well underway, and last night’s series of five primaries means that 10 states have chosen their party’s nominees for the November elections. And as primary season unfolds (19 more states will be holding their primaries between next Tuesday and June 28), there are additional signals that further clarify what JMC first noted on March 2 – that this looks like a strong Republican year.

When making such a qualitative assessment, JMC analyzes the following available data to best assess what lies ahead – as he has done in each midterm election starting with 2010:

- Partisan enthusiasm,

- Voter registration changes,

- The overall political climate.

Factor One – Partisan enthusiasm: Given that midterm election turnout is less than it is in Presidential election years, partisan enthusiasm takes on added importance, especially in close races. JMC believes that this enthusiasm can be quantified during primary season, provided that both parties have contested primaries for a statewide office like Governor or U.S. Senator.

When examining midterm data in 37 qualifying states between 2010 and 2018, JMC found that Republicans got 55% of the primary vote both in 2010 and 2014 (both were GOP landslide years). In 2018 (which was a Democratic landslide year), there was an 18-point swing to a 54% Democratic primary electorate. In other words, partisan primary party vote does have some predictive value.

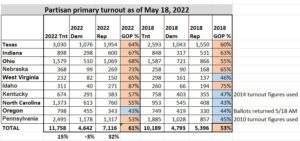

And what started with the Texas primary (a 60% Republican electorate in 2018 increasing to 65% in the March primary) has almost without exception been the case in the other nine primaries held between May 3 and last night. Not only has (in the 10 state contests analyzed) the Republican share of the electorate increased from 53 to 61%, but overall turnout has increased 15% (a 32% increase in Republican primary turnout coupled with a 3% decrease in Democratic turnout). Furthermore, from the standpoint of which party’s voters turned out in greater numbers, Republicans “flipped” Kentucky, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

It’s also worth noting that in politically marginal Georgia and North Carolina, the early vote in North Carolina (which had its primary last night) went from 59-41% Democratic in the 2018 primary to 50-49% Democratic this year. Similarly, in Georgia (which is in the middle of early voting for next Tuesday’s primary) saw its 2018 early voting electorate shift from 52-46 to 57-42% Republican between 2018 and 2022. In both instances, the early voting VOLUME was higher: double the 2018 numbers in North Carolina and (as of last night) triple in Georgia.

Factor Two – Voter registration changes: Partisan enthusiasm can be measured in another way: in states with voter registration by political party, the change in partisan voter registration since the Biden inauguration can be an additional barometer of whether or not the political winds have shifted.

And even when you consider that in an off year like 2021 voter files are being cleaned up to remove inactive voters, partisan trends were nonetheless apparent: between January and September 2021, Republicans lost nearly as many voters as Democrats did: there was a decrease of 1M Democrats and 853K Republicans in that time period (the number of Independents decreased 288K).

That trend suddenly changed between October 2021 and May 2022, when the number of Democrats declined another 628K, while the number of Republicans increased 51K, and the number of Independents increased 395K (for proper context, 122M registered voters were tracked in states with partisan voter registration). Regardless of how one wants to spin the data (more and more voters choosing to be unaffiliated versus a pickup in Republican voter registration activity), the fact is that neither trend is something the Democrats should feel good as we are in the midst of primary season.

Factor Three – The Overall Political Climate: This is another area where Democrats should remain concerned. Midterms are typically a referendum on the party in power, particularly the President (as the leader of his party). President Biden started off his tenure with a 53-36% approval rating; his approval rating went “underwater” in August after the Afghanistan withdrawal and hasn’t recovered since – his current aggregate approval rating is 53-41% disapprove (a 29-point shift in 17 months, with minimal change in recent months). Given that he was elected with 51% of the popular vote, a drop that substantial obviously signals a substantial defection from independent voters and/or soft partisans.

The feeling of discontent has been noted by Congressional Democrats, particularly in the House: with only 35/50 states concluding their candidate filing for the midterms, we already have 33 House Democrats (compared to 23 House Republicans) not seeking re-election. This is a volume of retirements only seen twice since 1978 (the last time more than 30 House members of the same party retired was in 2018, when Republicans left in large numbers in expectation of the massive blue wave which eventually occurred).

In addition to the factors listed above, there are some unknown factors that have not yet played themselves out. Candidate quality (i.e., the caliber of candidate each party chooses now that primary season is underway) will certainly play a part in the outcome of the November elections. Furthermore, while Biden’s approval ratings have been bad for months, that does not necessarily mean those numbers will remain bad throughout the year, but it does make the Democrats’ jobs much more difficult right now.

Conclusion: While the political climate favors Republicans at this point, we haven’t yet seen much general election polling showing how its candidates are performing in a general election environment. Still, there are enough “red signals” appearing (nearly three months into primary season) to be worth writing about.