While midterm elections are 8 months away, primary season kicked off last night in Texas (the first primary of the 2022 election cycle). Even with only one primary being held, there are some signals that can be discerned from the data at this point.

In assessing the extent of a possible partisan shift, JMC prefers to use the following available data to best assess what lies ahead:

- Partisan enthusiasm,

- Voter registration changes,

- The overall political climate.

Factor One – Partisan enthusiasm: Given that midterm election turnout is noticeably lower than in Presidential election years, partisan enthusiasm takes on added importance, especially in close races. JMC believes that this enthusiasm can be quantified during primary season, provided that both parties have contested primaries for a statewide office like Governor or U.S. Senator. When examining midterm data in 37 qualifying states between 2010 and 2018, JMC found that Republicans got 55% of the primary vote both in 2010 and 2014 (both were GOP landslide years). In 2018 (which was a Democratic landslide year), there was an 18-point swing to a 54% Democratic primary electorate. In other words, partisan primary party vote does have some predictive value.

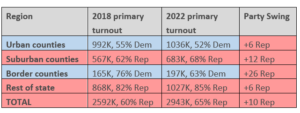

Meanwhile in Texas, a 60% Republican electorate in 2018 increased to 65% Republican last night with 95% of the vote counted. And within those numbers, partisan shifts between 2018 and 2020 are even more telling, since it became fashionable among Democratic pundits to assume that Texas was “turning blue”, thus causing them to pour a considerable amount of resources into the state in 2018 and 2020 in the pursuit of that goal.

From examining the data, two things should give Democrats pause: while it’s true that the partisan swing in the “urban core” counties was more modest, suburban counties moved noticeably back towards the Republicans, as did Hispanic counties south of San Antonio that have been ancestrally Democratic for years before substantially moving towards the Republicans between 2016 and 2020 (Clinton’s 61-36% win in those counties narrowed to 53-46% Biden four years later). There is also the matter of turnout, where Republican turnout surged more than Democratic turnout did between 2018 and 2022 (+23% for Republicans vs 0% change in Democratic turnout).

In addition to the Texas primary, there were also last November’s Virginia and New Jersey statewide elections. In Virginia, Republicans swept all three statewide races and regained control of the state House (state Senate races were not on the ballot); in New Jersey, the Democratic incumbent governor was nearly upset, and Republicans made noticeable gains in the Legislature for the first time since 1991. Since both of these states voted 54 and 57%, respectively, for Joe Biden, these reversals can’t solely be chalked up to the Republican base turning out – instead, it’s a case of noticeable erosion among Independent voters (in a recent ABC news poll, just 30% of Independents approved of Joe Biden’s job performance)

Incidentally, both Virginia and New Jersey saw noticeable partisan swings in 1993, 2009, and 2017 (the results were mixed in 2013), so these two states can serve as a bit of a “distant early warning” for either party well in advance of the midterms.

Factor Two – Voter registration changes: Partisan enthusiasm can be measured in another way: in states with voter registration by political party, the change in partisan voter registration since the Biden inauguration can be an additional barometer of whether or not the political winds have shifted.

And even when you consider that in an off year like 2021 voter files are being cleaned up to remove inactive voters, partisan trends were nonetheless apparent: between January and September 2021, Republicans lost nearly as many voters as Democrats did: there was a decrease of 1M Democrats and 853K Republicans in that time period (the number of Independents decreased 288K).

That trend suddenly changed between October 2021 and February 2022, when the number of Democrats declined another 212K, while the number of Republicans increased 50K, and the number of Independents increased 491K (for proper context, 122M registered voters were tracked in states with partisan voter registration). Regardless of how one wants to spin the data (more and more voters choosing to be unaffiliated versus a pickup in Republican voter registration activity), the fact is that neither trend is something the Democrats should feel good about at the beginning of primary season.

Factor Three – The Overall Political Climate: This is another area where Democrats should be concerned. Midterms are typically a referendum on the party in power, particularly the President (as the leader of his party). President Biden started off his tenure with a 53-36% approval rating; his approval rating went “underwater” in August after the Afghanistan withdrawal and hasn’t recovered since – his current aggregate approval rating is 53-41% disapprove (a 29-point shift in 13 months). Given that he was elected with 51% of the popular vote, a drop that substantial obviously means there was a substantial defection from independent voters and/or soft partisans.

The feeling of discontent has been noted by Congressional Democrats, particularly in the House: with only 8/50 states concluding their candidate filing for the midterms, we already have 31 House Democrats (compared to 16 House Republicans) not seeking re-election. This is a volume of retirements only seen twice since 1978 (the last time more than 30 House members of the same party retired was in 2018, when Republicans left in large numbers in expectation of the massive blue wave which eventually occurred).

In addition to the factors listed above, there are some unknown factors that have not yet played themselves out. Candidate quality (i.e., the caliber of candidate each party chooses now that primary season is underway) will certainly play a part in the outcome of the November elections. Furthermore, while Biden’s approval ratings have been bad for months, that does not necessarily mean those numbers will remain bad throughout the year, but it does make the Democrats’ jobs much more difficult right now.

Conclusion: While the political climate favors Republicans at this point, it’s still early in the political season. Still, there are enough “red signals” appearing to be worth writing about.