Introduction

We are in the midst of election season now; in fact, people are already voting in 31 states – that we know about, and the Vice Presidential debate between Tim Walz and JD Vance has concluded. And Election Day is just less than a month away.

Given that we’re past the halfway mark, what has been going on (from a polling perspective) with the Presidential race?

Presidential Polling

When discussing polling for the 2024 Presidential contest, the main challenge for the party in power/Democratic nominee Kamala Harris is that the Biden Administration remains unpopular (44-54% approval/disapproval according to a 7-day average of polls taken, which is a slight uptick from 43-54.5% last week). Since Kamala Harris is Joe Biden’s Vice-President, that obvious association with an unpopular President remains a negative weight on her campaign.

What has been characteristic of this election cycle is that supposed “big events” generally haven’t moved the needle much. The latest “big events” have been (1) the Vice-Presidential debate, and (2) Special Counsel Jack Smith filing a 165 page brief on Presidential immunity regarding former President Trump’s conduct on January 6. Which means that for the past six weeks, there has been an “equilibrium” of a national popular vote lead of 2-2.5% for Kamala Harris (which, incidentally, was the popular vote spread for the same 2016 Presidential election that initially elected Donald Trump).

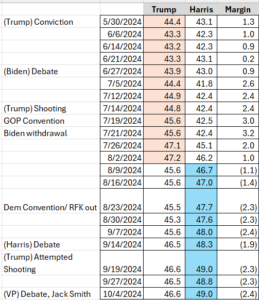

Despite the dictates of historical conventional wisdom, only two events have materially benefitted Kamala Harris’ campaign: (1) Biden’s withdrawal on July 21 (which caused a 3.2% Trump poll lead 10 weeks ago to shift 5.6% “to the left”) and, (2) to a lesser extent, Kamala’s debate performance on September 10. Currently, a 7-day average of national polling shows Harris up 2.4% (49-46.6%) over Donald Trump – a point spread almost identical to last week. To put this 2.4% lead for Harris in proper perspective, though, RealClearPolitics notes that at this point in time, Biden in 2020 was ahead of Trump by 9.1%, while Hillary Clinton was up 4.1% over Trump in 2016.

Below is a representation of the weekly changes in the national poll averages since late May:

National popular vote vs the Electoral College

When discussing the news value of “national popular vote polls”, it’s important to recognize that it’s the Electoral College (and not the national popular vote) that actually elects a President, and that marginally benefits Republicans due to an inefficient vote distribution of Democratic and Republican votes across the each state. In other words, a Republican can be elected President without attaining a popular vote majority (or even a plurality), because California and New York have in recent election cycles generated larger Democratic vote margins than Florida and Texas have for Republicans. And while large margins in California/New York “run up the (national popular vote) score”, “running up the score” doesn’t get a Democratic candidate any closer to the needed 270 electoral votes without winning critical swing states – winning critical swing states does.

To illustrate the disconnect between the Electoral College and the national popular vote, Joe Biden was elected in 2020 with a 4.5% popular vote margin (51.3-46.8%) over Donald Trump, but his victory was (using applicable 2024 numbers) a 303-235 Electoral College win (270 electoral votes are needed to win), Biden’s Electoral College victory was due to narrow victories in several states, like Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Using that 4.5% national popular vote win as a baseline, we can assess the extent to which shifts in the national popular vote towards Trump could flip specific swing states, as national shifts have an impact in both swing and non-swing states. To be conservative in his analysis, JMC is assuming that only half of a national popular vote shift (percentage-wise) occurs in a swing state, since those states (which get an oversized amount of attention from either side) are less elastic in their movement towards a candidate.

Even with this conservative analysis, any movement towards Trump relative to a 4.5% national popular vote deficit would “flip” states to Trump that narrowly voted for Biden in 2020. Even if Kamala Harris wins the national popular vote by 3.5% (a shift of only 1% towards Trump, in other words), Trump instantly flips Arizona and Georgia, and those two flips alone get Trump up to 262 electoral votes – 8 electoral votes shy of a victory. A Harris win of 2.5% (a 2% shift towards Trump relative to 2020) would also flip Wisconsin and get Trump to the necessary 270 electoral votes.

Let’s apply that theory to current polling numbers – a Harris lead of 2.4% would translate to 272 electoral votes for Trump. In other words, a 2.4% Harris lead equals a 2.1% swing to Trump relative to his 2020 popular vote loss. A swing of that magnitude (even accounting for swing states’ inelasticity relative to the rest of the country) would flip Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin and give Trump the electoral votes he needs to win. Below is a representation of the electoral college impact of various national popular vote possibilities.

There is another aspect to polling that needs to be considered: quantifying previous years’ polling errors in swing states, as those errors both in 2016 and 2020 almost without exception understated the Trump vote. If we were to examine how far the average of last week polls were “off”, and factor that error into the average of current polling over the last 7 days, what we find is that Trump can (based on current polling) flip Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Assuming that polling accuracy has not improved since 2016/2020, those flips would get him (under this hypothetical example) 306 electoral votes.

The early vote

While technically Election Day is November 5, an increasing number of voters are choosing to vote before that. Research done shows that 45% voted early in 2016, and that number surged to 69% in 2020. While the pandemic/mass adoption of mail voting certainly contributed to the increase in early voting in 2020, the reality is, Election Day voting is nevertheless becoming a thing of the past for an increasing number of people, which DOES impact the timing of when campaigns need to disseminate their messaging to voters.

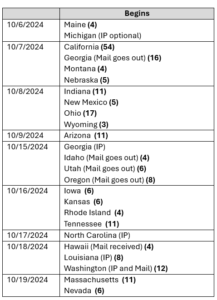

This past week was relatively quiet with regards to the early voting calendar: before that, several swingy states (Florida, North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) sent out mail in ballots, while Illinois, Virginia, and New Jersey sent mail ballots out as well. In person early voting has also begun in two “swingy” states (Minnesota and Virginia), while three other states (Illinois, North Dakota, and South Dakota) have begun in person early voting as well. Below is a calendar of the next 14 days of early voting:

Early Voting Data

Currently, we have data on mail ballot requests in 36 states, and currently, 53 million (up from 51.1M a week ago) have already requested a mail in ballot. Furthermore, 1,700,462 in 30 states have already voted either by mail or in person (compared to 402,245 a week ago). These figures will skyrocket very soon, as in person early voting starts in several states like Arizona, New Mexico, and Ohio, while mail ballots will go out in California and Georgia (in person early voting commences in Louisiana Friday, October 18).

Conclusion

Even though Republicans have remained in a two point deficit in the national popular vote since the Biden withdrawal, polling numbers have stabilized with a Harris lead small enough to make it possible for Donald Trump to amass 270 electoral votes. And polling numbers don’t factor in the possibility for “misses” which both in 2016 and 2020 understated the Trump vote.

Meanwhile, early voting continues to accelerate, which means in practical terms that the peak of campaign season (in terms of reaching the maximum number of movable voters) is happening now, because as states are steadily ramping up their early voting throughout the month, those who have voted become irrelevant to either campaign from either a persuasion or a turnout perspective.